Financial Accountability Regime (FAR) – If all you've done is signed an Accountability Statement, you're not prepared

The replacement of the Banking Executive Accountability Regime (BEAR) with the Financial Accountability Regime (FAR) which came into effect in March this year, provides us with a timely reminder of the financial, personal, professional and legal consequences of organisational failures. As a senior executive who may have already prepared and signed an Accountability Statement for APRA, it is understandable that you might be asking yourself “what could all this mean for me?” In our view, if you have approached the Financial Accountability Regime (FAR) with a ‘tick the regulatory box’ approach, then it is more than likely you haven’t done enough.

While we have covered the issues around FAR and operating models in organisations previously in our blog, in this article we have four areas for Senior Executives in banking, finance, superannuation and insurance companies subject to the regime to consider:

The case for a more accountable organisation

Defining the playing field

Defining what it means to be accountable

Lining the organisation up behind you.

1. The case for a more accountable organisation

Before we dive into the detail, let’s take a big step back. One of the Hayne Royal Commission recommendations (published in 2019) was to drive a ‘culture of accountability’ within our financial institutions. APRA, as the regulator, embodied this insight in BEAR and then FAR with significant breaches (for financial institutions) and disqualification of accountable persons (for individuals). But to suggest that adopting FAR will imbue your business with a newfound sense of accountability is like suggesting that having a driving licence makes you a Formula 1 driver. Sure, you need the licence to drive, but there’s so much more you need to do before you can line up on the starting grid.

Like any major change in any organisation, the same rules apply – you need your most senior leaders to completely understand that change is necessary (the ‘case for change’), and you need to be aligned behind a common, compelling vision (the ‘future state vision’). If your organisation’s case for change is “APRA is telling us” and your vision is “We will comply”, then unfortunately you aren’t on the path to a culture of genuine accountability. To extend the Formula 1 analogy, you’re going to get your P’s and be constrained to doing donuts in a McDonalds car park.

But here’s the good news – building a culture of accountability is good for you, for your business, and most definitely for your customers. With or without a regulator and FAR, implementing a system that drives outcomes, measures performance, and clearly assigns responsibility and ways of working IS good business.

As senior executives, that’s where you need to start – with a common, deeply held belief that your investment in accountability as a cultural asset is a commercial (not regulatory) imperative.

2. Define the playing field

There’s more good news. When we refer to a ‘culture of accountability’, there is a well-defined framework to structure your effort around. While usual talk around culture may convey a fuzzy, unclear concept that you consign to your HR department, your effort to define and manage a high-performance organisation around accountability should be a clear process centred around value and outcomes.

Before going ahead and defining who is accountable for what in your business, you need to start with defining the playing field. As a leadership team, how exactly do you define and discuss WHAT your business does, end-to-end, to generate value? If you view your Accountability Statements as a puzzle piece, and each senior executive is holding one piece, how do you efficiently and effectively understand how each piece fits together if you aren’t all staring at the same picture on the puzzle box?

APRA has provided some suggested functional areas that should be covered in an Accountability Statement (view APRA’s advice here). However, with due respect to the regulator and recognising that it has been developed as a guideline only, the laundry list of tasks covered in the guidelines doesn’t reflect the complete picture or the variances between different businesses. For example, there’s nothing in the guideline that refers specifically to sales, customer service or marketing – the closest we can infer is a single line reference to “Product design, development and distribution, compliance and reserving including framework, strategy, policies, procedures and assessment”. This is troubling when, arguably, how the front line, consumer-facing financial services workforce has behaved with customers has generated the most outrage in the public and the media.

From a legal and risk perspective, there may be some good reasons to limit how broadly you define the playing field. But, in reality, just because you don’t cover those areas in your Accountability Statements, doesn’t mean your accountability for them – and your need to manage them – diminishes. Our advice is to define the whole business first, using a value chain or similar organising framework (that may already exist internally), that clearly defines WHAT your organisation does and how it relates to the rest of your business.

3. Defining what it means to be accountable

At this point in the blog, I’d like to invite you to conduct an experiment. Ask your senior colleagues to independently define what is meant by “accountability”. What you might quickly realise is that, on a practical level, we all kind of know what is meant by accountability, but we differ in how we define and apply the concept. We use it interchangeably with other words, like responsibility, or ownership, or stewardship. What we hold in our heads to mean accountable will invariably be broader or narrower, shallower or deeper, than others in our organisation and in the broader public.

APRA seems to be mixed in its advice on accountability too, encouraging organisations to take a relatively loose approach to the issue and break what we consider to be a cardinal rule of good organisational design (i.e. don’t have multiple people responsible for the same thing). In response to the question of sharing accountability, they have this to say:

“The legislation permits joint responsibilities. Nevertheless, APRA considers individual accountability to be the clearest form of accountability. Where multiple accountable persons have the same particular responsibility, ADIs can nominate the individuals as jointly accountable, meaning they are equally accountable with respect to that particular responsibility.”

Besides switching between the terms accountable and responsible, which we take to mean different things, they fall into a common trap in poor organisation design – as we like to say, if everyone is responsible, then no one is.

So, our advice is clear – just as we would do with any operating model discussion, we would introduce and encourage very prescriptive terms to describe accountability, responsibility and concepts like inter-dependence. By being prescriptive, you’re driving alignment and reducing confusion. It also serves as the foundation for establishing ways of working to support your accountability regime.

Accountability, Responsibility and the role of Governance and Interactions.

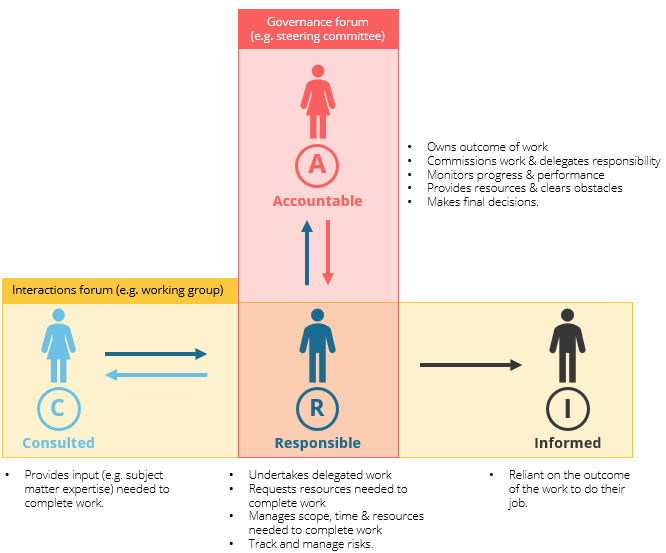

From an organisation design perspective, accountability refers to an individual function or role that it has to deliver an organisational outcome, e.g. a Marketing executive who is accountable for customer acquisition. Accountable roles have the authority to delegate responsibility for the delivery of work and play a critical role in managing performance, ensuring outcomes are delivered and ensuring there are appropriate checks and balances (i.e. governance and interactions) in place to support service delivery (see Figure 1 below for a simple overview). Simply put, they are different and separate. You can’t have more than one accountable or responsible, nor should the same role be both accountable and responsible for the same thing. You’d effectively be marking your own homework, duplicating effort and diluting visibility of where accountability lies.

Figure 1: Governance and interactions forums.

4. Lining the organisation up behind you

In any organisation, taking accountability or responsibility for something means that you are dependent on others. Unless you build and manage your own ‘fiefdom’ with all the levers of your performance solely in your control, as a senior executive you will invariably be reliant on others to perform certain tasks on your behalf. As a product manager, you are reliant on the sales force to accurately represent your product favourably to your consumers, and as a sales executive, you’re reliant on marketing to get the message right so that you have consumers interested in your products and services.

The nature of that interdependence takes on even greater meaning if you’ve just signed an Accountability Statement and submitted it to the regulator. Do you have the organisational systems and ways of working behind you to ensure you are able to deliver your accountability? If your answer isn’t a resounding yes, then it may be time to work on your organisation’s operating model, or more simply your “ways of working”.

Organisations who invest in establishing clear ways of working (as defined by their operating model) can improve accountability, employee engagement, governance, and reduce opportunity for risk taking behaviour. Often misinterpreted for organisation structure, the operating model provides a systematic method of understanding what the organisation does and how they operate to deliver value to customers. The basis of any good operating model includes:

A clear articulation of your core purpose and what the organisation does to deliver value (i.e. the value chain including key outcomes and performance measures)

Clearly defined roles and responsibilities (e.g. agreement on who is accountable for the outcome, responsible for doing the work and who needs to be consulted or informed when making decisions)

A governance framework that defines how different functions/roles will work together to manage performance and address risk (e.g. the governance forums needed to make key decisions)

An organisation structure that defines the core capabilities, capacity and optimal configuration of roles required to bring the operating model to life (e.g. the people and organisation needed to make the operating model a reality)

Enabling capabilities (e.g. business processes, technology and information management).

The good thing for leaders in financial services right now is that much of the work has already been done and there is momentum for change. There has never been a time where the case for change is clearer than what is being presented in the media today. Given this, we propose the starting point for leaders to achieve genuine cultural change is to redefine their operating model, value and what accountability actually means in their business.

Find out more about our operating model and organisation design work here.

Want to talk to us about how we can help you with your FAR work? Reach out to:

Fadi Zeitoune, principal

clare morris, director